Table of Contents

AC 1.1 An Evaluation of Both the Aims and at Least Three Objectives of Employment Regulation

Most laws and regulations on employment are written from the perspective of the worker. They are frequently put in place to perform a variety of things, such as a guarantee that workers are treated fairly, that government policy is implemented, that social and economic goals are met, and that a business is complying with international legal commitments.

Protection of Employees

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is widely acknowledged as having a vital role in establishing the goals of international employee legislation, with a focus on worker protection (Factorial HR, 2022). The International Labour Organization (ILO) established an employment protection law that was accepted by several nations including the United Kingdom. This legislation protects workers against discrimination and workplace injury. Accordingly, employers have a responsibility to shield their employees from any form of discrimination based on factors such as race, colour, or religion. The Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 safeguards workers in the workplace by ensuring that workplaces are safe and supply PPE to their staff (HSE, 2020).

Fairness

Equality Act 2010 ensures equal chances and eradicates discrimination promoting fairness in the workplace (Factorial HR, 2022). The laws established by employment law are essential for proving that compensation and benefits are equitable. It also ensures that employees are treated properly and diversity and equality are more appreciated and respected when there is a culture of justice in the workplace. Furthermore, the act ensures that employees are paid following the agreements they made with their employers.

Justice

Equality Act 2010 establishes the basis for judicial jurisdiction by determining whether or not the termination of an employee’s employment followed the correct processes and was fair or unjust (Factorial HR, 2022). Employees are at risk of being terminated unfairly if not given procedural fairness in their termination process. Therefore, the regulation requires the employer to give the employee a reasonable opportunity to respond to allegations, seriously consider the claims that the employer is making against them, and then make a decision regarding a suitable penalty, which may include termination of employment terms based on evidence.

AC 1.2 An Examination of the Role Played by the Tribunal and Courts System in Enforcing Employment Law Covering the Hierarchy of the Court System in the UK

Employment Tribunals are a type of independent judicial body set up to hear cases involving potential violations of an employer’s rights by an employee (CIPD, 2022). Wrongful termination, discrimination, wages, and severance pay are common cases solved in court. Tribunals operate with a greater degree of informality and employment tribunal cases that are appealed often move to the Employment Appeal Tribunal, and from there to the court of appeals and ultimately the Supreme Court.

An unsuccessful party can seek a review of a judgement or decision by appealing to the presiding tribunal. The opposite party may appeal to the Employment Appeal Tribunal if it believes the tribunal did not appropriately apply the law or that the review process was flawed. In the event of a loss, the losing party has 21 days to file an appeal with the Court of Appeals (Suff, 2022). If the result still does not sit right with the complaint, they can take it up with the Supreme Court, but they will have to present their case strictly on legal grounds, showing that the law was not followed by the lower courts. And it only considers appeals in the most significant matters that affect the general public. If nothing else, it is the last resort for criminal and civil issues. Any national court or tribunal in Europe can seek a judgement from the European Court of Justice, as it is the highest court in Europe. However, it only hears cases like these if they involve European labour rules. The judicial equivalent of the administrative employment tribunals is the court system, where cases are initially heard at the county level and then moved to higher courts if an appeal is filed.

AC 1.3 An Explanation of How:

Employment Cases are Settled in Terms of The Role of Acas and Use of Cot3 (Gb) and the Early Conciliation Process Before the Start of Proceedings

The Employment Rights Act of 1996 details the processes for resolving employment-related disputes. It is strongly advised that before going to an employment tribunal, an employee first submit a formal complaint to the ACAS. ACAS may mediate workplace disagreements if both parties agree to its involvement. ACAS’s goal is to help the parties reach a mutually agreeable resolution to the dispute. When ACAS identifies the cause of the conflict and gives each side a chance to air their grievances, it has fulfilled its mission.

ACAS may first step in when a claimant announces their intention to claim to ascertain whether or not the claimant is interested in early conciliation (Davidsonmorris, 2020). If the employee is willing to participate in early conciliation, ACAS will request information from them. A follow-up communication, an email, letter, or phone call detailing the individual’s final decision and the nature of the dispute is required. The conciliator will then interact with the complaint to get insight into the complainant’s desired resolution. After receiving confirmation from the responder, the conciliator will initiate communication between the parties to resolve. As soon as a settlement is reached, the conciliator will write a formal agreement using the COT3 form and underline the parameters of the agreement (Davidsonmorris, 2020). When all parties sign a COT3 agreement, the tribunal concludes the case.

Cases are Setting During Formal Legal Proceedings in Terms of Settlement Agreements

When a case is settled during formal legal proceedings, the parties will negotiate and determine the terms of a settlement agreement. This can be done through mediation or arbitration (Pon Staff, 2021). If the parties agree, then all procedural steps are taken to apply for that settlement on behalf of the client and move on to other cases or business activities with complete certainty that the case has been resolved. Mediation entails selecting a third party with no stake in the outcome of the dispute to act as an impartial arbiter. They instead pose a series of questions to both the employer and the employee to get to the bottom of the matter at hand. They help both parties identify the core issues at play and work together to achieve a mutually agreeable resolution. The primary goal of mediation in a work setting is to keep the working relationship between the employer and employee at the same level it was before the conflict arose. Arbitration is a process in which an impartial person is hired to hear both the arguments and grievances of the parties involved and come to a decision on their own. The arbitrator then sits with both parties and addresses the case in a fair fashion that works out the best for both parties involved.

Evaluating the principles of discrimination law in recruitment, selection, and employment (AC 2.1)

Selecting the most qualified candidate for a position requires a selection process that is fair, objective, and nondiscriminatory. In the course of this procedure, any practices that discriminate against certain groups will be seen as unfair (Macdonald, n.d.). For instance, employers are not permitted to inquire about a candidate’s protected characteristics, marital status, civil union status, or if they are a parent or intend to become one (“Employment status I GOV.UK”, n.d.). The right to be treated equally and not be discriminated against because of a protected characteristic is a fundamental human right. Age, handicap, gender reassignment, marriage/civil union, pregnancy/maternity, race/ethnicity/belief, sex, and sexual preference are all protected categories (McKevitt, n.d.). The complainant in Scenario 1 very certainly had their offer rescinded due to one of the aforementioned qualities, making their case disputable before an employment tribunal. The Equality Act of 2010 makes it illegal to discriminate against someone either directly or indirectly, as well as to victimize someone. For example, if it was anticipated that the worker would be unable to function due to their civil partnership, this might be classified as direct discrimination in which an individual regards the other as less favorably compared to how the same person treats or would treat his/her fellows because of the protected trait of marriage or civil partnership (McKevitt, n.d.). Employers are prohibited by the Equality Act of 2010 from discriminating against job candidates based on a protected characteristic. Furthermore, refusing to hire a job candidate based on protected characteristics constitutes blatant discrimination. In regard to disability, the Equality Act of 2010 safeguards disabled employees at all stages of their job (Macdonald, n.d.). If a company can demonstrate that a certain work can be done successfully exclusively by a person with a certain impairment, then the employer will not be in violation of the discrimination statute. Furthermore, the law limits an employer’s capacity to conduct pre-employment health inquiries (Macdonald, n.d.). An employer shall not discriminate against a disabled employee due to a circumstance related to their disability.

The legal requirements in relation to defending equal pay claims and conducting equal pay reviews (AC 2.2)

There should be no wage gap between men and women who do equivalent work, as mandated by the Equality Act of 2010, unless there are compelling reasons for such a gap. (Suff, 2021). Employers are obligated to comply with this regulation since it is the law. Failure to provide fair compensation may result in a costly employment tribunal lawsuit.

There should be no wage gap between men and women who do equivalent work, as mandated by the Equality Act of 2010, unless there are compelling reasons for such a gap. (Suff, 2021). Employers are obligated to comply with this regulation since it is the law. Failure to provide fair compensation may result in a costly employment tribunal lawsuit.

‘Equal work’ is defined by law as either

- ‘Like work’ – employment where the duties and skills are identical or comparable

- ‘Work rated as equivalent’ – work deemed equivalent, typically based on a reasonable job evaluation. This could be due to the fact that the talent, responsibility, and effort required to complete the tasks are equivalent (McKevitt, n.d.).

- ‘Work of equal value’ – Work that is distinct but of equal worth. This may be due to the fact that the degree of ability, experience, responsibility, and expectations of the job are of equivalent value (Suff, 2021).

If a gender pay gap exists an employer must demonstrate that there is a “material element” that accounts for the difference in pay. Moreover, for the material to be considered relevant it must;

- entail a valid reason for the disparity in compensation

- Be important and pertinent.

- Clarify the pay disparity with ‘specificity,’ which implies the employer must be able to demonstrate how each consideration was weighed and demonstrated how it fit in the woman’s specific circumstance.

- It must be free of blatant and indirect sex discrimination.

Hence, if the woman in ARL is better skilled and qualified for a position than the males who are performing the same task, then it may be appropriate for her to receive a higher salary than the men. If there is an equal pay issue ARL is required to demonstrate, that the female’s qualifications and talents are essential for the work, and that they had trouble hiring and retaining employees for the position that the woman now has. However, the fact that they get paid more cannot be related in any way to their sexual orientation.

Explaining the major statutory rights workers have in relation to pay ( AC 4.1)

When it comes to employment law, statutory rights are meant to safeguard the interests of both employers and employees, giving either party a footing on which to pursue legal action. Under the UK law, all employees are entitled particular statutory rights, despite the fact that the applicability of the rights varies. For instance, the entitlement to redundancy pay or compensation for a wrongful dismissal only becomes vested after a specified amount of time has passed. The following are some key concerns that rights workers have in regard to pay:

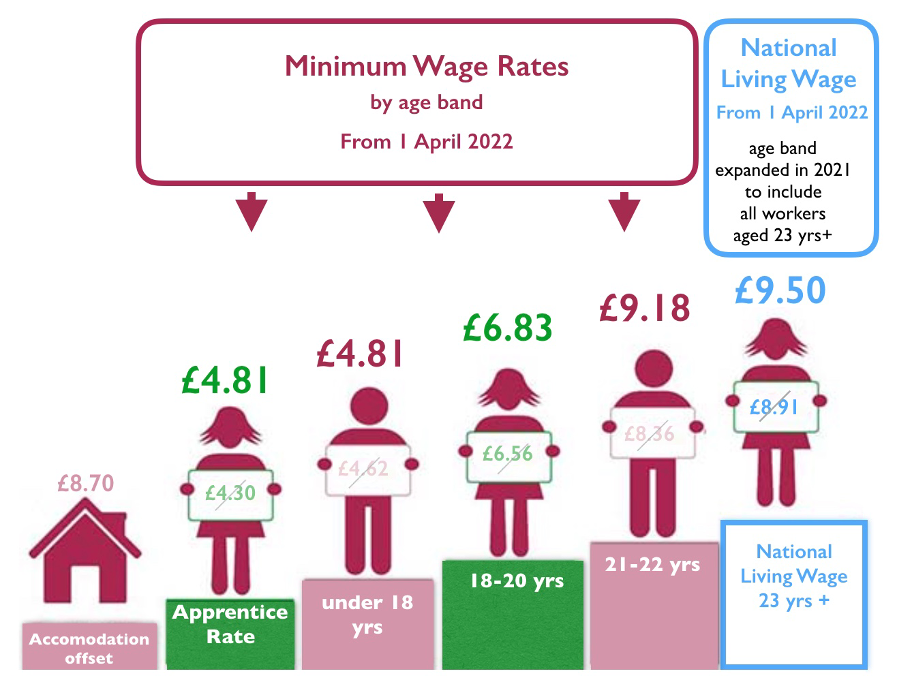

Getting the National Minimum Wage; the minimum salary for a worker should vary based on their age and whether or not they are apprentices (“The National Minimum Wage and Living Wage”, n.d.). Workers in almost all industries are guaranteed at least the National Minimum Wage per hour. Worker eligibility for the National Living Wage, which is higher than the National Minimum Wage, depends on their age, and workers must be at least 23 years old to qualify for it. Employers, regardless of their size, are required to pay the exact minimum wage.

Statutory sick pay: If an employee is unable to work due to illness, he/she is eligible to receive Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), which is currently set at £99.35 per week. It is paid by the employer for a maximum of 28 weeks (Gov.Uk). An individual cannot receive less than the legal minimum. If the employer offers a sick pay program, sometimes known as an “occupational plan,” an employee may be able to get extra.

Statutory sick pay: If an employee is unable to work due to illness, he/she is eligible to receive Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), which is currently set at £99.35 per week. It is paid by the employer for a maximum of 28 weeks (Gov.Uk). An individual cannot receive less than the legal minimum. If the employer offers a sick pay program, sometimes known as an “occupational plan,” an employee may be able to get extra.

Statutory redundancy pay: Employees with two years or more of service are typically eligible for statutory redundancy pay from their employers. That is, if an employee works for a full year and is under the age of 22, they shall receive half a week’s salary, if they work for a full year between the age of 22 and 41, they will receive a full week’s salary, and if they work for a full year and are over the age of 41, they will receive a full week and a half’s salary (Gov.Uk). The maximum term of service is 20 years. Notate that the employee’s weekly compensation is the average amount they earned per week over the previous 12 weeks prior to the day they received their notice of layoff (Gov.Uk).

Discussing the legal implications of managing the change in relation to the working hours ( AC 3.1)

The 1998 Working Time Regulations (WTR) governs work hours in the United Kingdom. These restrict employees to a maximum of 8 hours of labor per day and a maximum of 48 hours per week (however workers in the United Kingdom can opt out of the regulations pertaining to the required 48-hour work week). Nonetheless, the pandemic has had a profound impact on working hour’s data (“Contracts of employment and working hours – GOV.UK”, n.d.). The average number of paid hours worked per week in the United Kingdom rose by 1.8 hours between the third and fourth quarters of 2020, according to data provided by the Office for National Statistics in February 2021.

Nevertheless, under UK legislation, employers are required to protect the health and safety of all employees, which includes protecting them against overwork and long hours. The WTR currently provides the following fundamental rights and safeguards to employees:

- A maximum of 48 hours per week averaged over 17 weeks that an individual is be obligated to work.

- Night employees are only allowed to put in an average of eight hours of work each twenty-four-hour period.

- The right to receive 11 hours of rest each day.

- An entitlement to one day off every week (Suff, 2021).

- A right to an on-the-job rest period if the work schedule exceeds six hours.

- Annual paid leave of 28 days for full-time employees (Suff, 2021).

Scenario three is a clear violation of workers’ rights under the Working Time Regulations 1998, since it calls for ARL employees to work 12 hours per day or 84 hours per week, rather than the standard 8 hours per day/48 hours per week. On the other hand, ARL has the ability to get its employees to sign what is known as an opting-out agreement, which requests employees to consent to working more than 48 hours in a week. However, it is vital to highlight that companies cannot compel workers to sign an opt-out: employees should willingly consent to it, and they cannot be fired for not signing one (“Contracts of employment and working hours – GOV.UK”, n.d.).

Explaining the legal requirements relating to the transfer of undertakings ( AC 3.2)

A transfer of undertakings (TUPE) occurs whenever there is a change in the company’s ownership or service provider. The Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006 (TUPE) ensures that employees in the UK continue to enjoy the same or comparable terms and conditions of employment in the event of a “relevant transfer” such as the sale of a business (Suff, 2022).

Transferors must undertake comprehensive, meaningful conversations with employees as soon as possible. In contrast to collective redundancy consultation, there is no minimum consultation period mandated prior to a transfer. Employers who fail to engage effectively may be obliged to compensate employees for up to 13 weeks of pay. Both the person making the transfer and the person receiving it are responsible for making this payment (Suff, 2022). The transferee assumes responsibility for all statutory rights, claims, and obligations, including those originating from the contract, tort liability, unjust termination, equal pay, and discrimination claims. Excepted from this regulation are criminal liabilities. The law prohibits employees and employers from “contracting out” of the requirements, hence it is impossible to avoid the application of TUPE. It may be feasible to arrange warranties and indemnities that soften the financial impact of any lawsuits emerging from the application of TUPE, either partially or entirely.

Any dismissals due to a transfer are inevitably unjust unless the firm can demonstrate a “economic, technological, or organizational” (ETO) basis necessitating a workforce change. There may be (ETO) justifications for a transferee’s unwillingness to accept the transferor’s workforce (Suff, 2022). Additionally, TUPE authorizes limited modifications to terms and conditions when there is an ETO rationale. In cases where an ETO reason is the primary factor leading to termination, the termination may be warranted if the transferee may be shown to have acted appropriately under the circumstances (Suff, 2022). Reasons for Early Termination of Employment (ETO) can range from economic factors like a significant decrease in productivity that makes business unsustainable without layoffs to technological factors like the introduction of new machinery that significantly reduces the demand for human workers (technical) (Suff, 2022). Regardless of whether there is an ETO justification, the standard legislation and practice regarding redundancy and unfair terminations will continue to apply (Suff, 2022). The economic (or other) grounds may be contested if there was no actual change in the job responsibilities or the quantity of employees.

Any dismissals due to a transfer are inevitably unjust unless the firm can demonstrate a “economic, technological, or organizational” (ETO) basis necessitating a workforce change. There may be (ETO) justifications for a transferee’s unwillingness to accept the transferor’s workforce (Suff, 2022). Additionally, TUPE authorizes limited modifications to terms and conditions when there is an ETO rationale. In cases where an ETO reason is the primary factor leading to termination, the termination may be warranted if the transferee may be shown to have acted appropriately under the circumstances (Suff, 2022). Reasons for Early Termination of Employment (ETO) can range from economic factors like a significant decrease in productivity that makes business unsustainable without layoffs to technological factors like the introduction of new machinery that significantly reduces the demand for human workers (technical) (Suff, 2022). Regardless of whether there is an ETO justification, the standard legislation and practice regarding redundancy and unfair terminations will continue to apply (Suff, 2022). The economic (or other) grounds may be contested if there was no actual change in the job responsibilities or the quantity of employees.

Explaining the major statutory rights in leave and working time ( AC 4.2)

The WTH regulations establish minimum requirements for weekly work time, rest benefits, and annual leave, as well as making special provisions for night employees. For example, practically all employees have the right, under the law, to 5.6 weeks of paid vacation time every year. Workers under zero-hours contracts, agency employees, or with unpredictable schedules fall into this category (“Holiday Entitlement & Pay | CIPD”, n.d.). It is essential to remember that the pandemic (COVID-19) does not influence employees’ eligibility to paid holidays and leave, with the exception of leave carryover.

According to the law, the majority of employees who work a standard 5-day workweek are required to receive at least 28 days’ worth of paid yearly leave each year. This equates to around 5.6 weeks of vacation time (“Holiday Entitlement & Pay | CIPD”, n.d.). While part-time employees have the right to at least 5.6 weeks’ worth of paid vacation time, although the total number of days will be less than 28 (“Holiday Entitlement & Pay | CIPD”, n.d.). However, statutory paid vacation days are limited to 28 days. Consequently, an ARL employee who opts out of the usual 48-hour workweek and works seven days per week is still eligible to 28 days of paid leave, as is an employee who chooses to continue working five days per week. However, ARL can grant additional leave than the minimum required by law. But they are not required to apply all statutory leave requirements to the additional leave.

Every employee over the age of 18 should be given at least three types of breaks per week: rest breaks at the workplace, a daily break, and a weekly rest. An unpaid 20-minute break is granted to workers who put in more than six hours of work per day (“Contracts of employment and working hours – GOV.UK”, n.d.). Whether or not they are compensated for the time-off is up to the terms of their work agreement. Regarding daily break, employees are entitled to 11 hours of respite between working days (“Contracts of employment and working hours – GOV.UK”, n.d.). Finally, employees are entitled to either a weekly period of 24 hours off from work or a biweekly period of 48 hours off from work. ARL must take into account these statutory rights when creating the working hours contract to minimize disagreements and litigations. An employer is required to provide sufficient breaks for employees to ensure their health and safety.

Every employee over the age of 18 should be given at least three types of breaks per week: rest breaks at the workplace, a daily break, and a weekly rest. An unpaid 20-minute break is granted to workers who put in more than six hours of work per day (“Contracts of employment and working hours – GOV.UK”, n.d.). Whether or not they are compensated for the time-off is up to the terms of their work agreement. Regarding daily break, employees are entitled to 11 hours of respite between working days (“Contracts of employment and working hours – GOV.UK”, n.d.). Finally, employees are entitled to either a weekly period of 24 hours off from work or a biweekly period of 48 hours off from work. ARL must take into account these statutory rights when creating the working hours contract to minimize disagreements and litigations. An employer is required to provide sufficient breaks for employees to ensure their health and safety.

Explain other employment rights relating to flexible working ( AC 4.4)

In order to alter its long-hours culture, ARL should think about implementing more flexible working hours for its employees. It is important for ARL’s management to be aware that after 26 weeks of employment, every employee has the right to seek flexible scheduling (McCartney, 2022). The ‘right to seek flexible working,’ previously available only to parents and certain workers in particular fields, was introduced by the British government in April 2003 (McCartney, 2022). Regardless of whether or not they have children, all employees who have been with their current employer for at least 26 weeks are now covered by the law. Employers are required to evaluate requests for flexible working in a rational manner and may only deny such requests if they can demonstrate that one of a limited number of causes applies (McCartney, 2022). Employers in the United Kingdom feel that the freedom to request flexible working law has been successful in raising the number of employees who take use of flexible work options in their organization. The (CIPD) believes more individuals would take use of flexible work options including part-time work, compressed hours, and job sharing if they had the legal right to seek them from the start (McCartney, 2022). Making it mandatory for all employees from the start should improve its efficiency by boosting its availability and uptake.

Explain the main principles of maternity, paternity, and adoption rights in the context of employment rights ( AC 4.3)

Explain the main principles of maternity, paternity, and adoption rights in the context of employment rights ( AC 4.3)

Paternity, maternity, or adoption leave and pay, as well as shared parental leave, should be guaranteed to all biological and adoptive parents (Suff, 2022). Other key ‘family-friendly’ policies include the opportunity to appeal for flexible work hours, time off for unexpected crises affecting dependents, and unpaid parental leave.

Maternity Rights

Maternity Leave

When an employee is pregnant, they are entitled to take off work for prenatal care and any additional appointments their doctor, nurse, or midwife deems necessary. The eleventh week prior to the due date is the earliest a woman can begin her leave for the birth of her child (Suff, 2022). The woman is obligated to provide her employer with information regarding her due date and her desired leave start date. The employer must answer within 28 days with the anticipated date of the employee’s return from maternity leave (Suff, 2022). Employers should presume that all 52 weeks of leave will be utilized unless they are advised otherwise.

Maternity Pay

Mothers are eligible for up to 39 weeks of Statutory Maternity Pay (SMP) if they meet the following requirements: Meet specified minimum earnings requirements for National Insurance contributions (Suff, 2022). Have worked nonstop for the past 26 weeks and assessed on the 15th before the baby is due. 90% of the average weekly wage is paid as SMP for the first six weeks, while the remaining weeks are paid at the lower statutory rate (Suff, 2022).

Additional rights, include;

- If their maternity leave is fewer than 26 weeks, women are entitled to return to their old position with no changes in pay or benefits.

- Women who take longer than 26 weeks out for maternity leave should be permitted to return to their previous positions, or be offered suitable alternatives if doing so would be unrealistic under the circumstances.

Paternity Rights

Paternity leave

The primary eligibility requirements for paternity leave:

- An employee can only be eligible for paternity leave if he or she is the child’s biological father or the mother’s partner who has or will have legal custody of the child.

- Holding down a job for the full 26 weeks leading up to the due date, and continuing until the 15th week of pregnancy.

Employees who are eligible for paternity leave are entitled to:

- Resuming the same position.

- Get back to working under the same conditions as before (Suff, 2022).

- Not be discriminated against, treated poorly, or fired without just cause.

Adoption Rights

Since April 2015, the United Kingdom has provided up to 52 weeks of paid statutory adoption leave, making it comparable to the length of statutory maternity leave (Suff, 2022). A minimum of 26 weeks of continuous employment is required to be eligible for Statutory Adoption Pay (SAP), which is paid out over a period of 39 weeks.

References

Contracts of employment and working hours - GOV.UK. Gov.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/browse/employing-people/contracts. Employment status. GOV.UK. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/employment-status/worker. Employment Law Updates UK | CIPD. CIPD. (2022). Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/about/legislation-updates#gref. Holiday Entitlement & Pay | CIPD. CIPD. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/holidays. McCartney, C. 2022. Flexible Working Practices | Factsheets | CIPD. CIPD. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/flexible-working/factsheet#6661. Macdonald, L. Discrimination in recruitment and selection | Recruitment and selection | Employment law manual | Tools | XpertHR.co.uk. Xperthr.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.xperthr.co.uk/employment-law-manual/discrimination-in-recruitment-and-selection/157530/. McKevitt, T. Marriage and civil partnership discrimination | Equality and human rights | Employment law manual | Tools | XpertHR.co.uk. Xperthr.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.xperthr.co.uk/employment-law-manual/marriage-and-civil-partnership-discrimination/105268/#justification Suff, R. 2022. Maternity, Paternity & Adoption Rights | Factsheets | CIPD. CIPD. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/maternity-paternity-rights/factsheet#gref. Suff, R. 2022. TUPE (Transfer of Undertakings) | Factsheets | CIPD. CIPD. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/tupe/factsheet#7094. The National Minimum Wage and Living Wage. GOV.UK. Retrieved 31 August 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/national-minimum-wage. CIPD, 2021. UK Court System & Employment Law | Factsheets | CIPD. [online] CIPD. Available at: <https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/about/uk-court-system-factsheet> [Accessed 31 August 2022]. Davidsonmorris, 2020. COT3 Agreement (Settlement FAQs). [online] Davidsonmorris.com. Available at: <https://www.davidsonmorris.com/cot3/> [Accessed 31 August 2022]. Factorial HR, 2022. UK Employment Laws – Everything You Need to Know. [online] Factorial HR. Available at: <https://factorialhr.co.uk/blog/uk-employment-laws/> [Accessed 31 August 2022]. HSE, 2020. Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 – legislation explained. [online] Hse.gov.uk. Available at: <https://www.hse.gov.uk/legislation/hswa.htm#:> [Accessed 31 August 2022]. Pon Staff, 2021. What are the Three Basic Types of Dispute Resolution? What to Know About Mediation, Arbitration, and Litigation. [online] PON - Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Available at: <https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/dispute-resolution/what-are-the-three-basic-types-of-dispute-resolution-what-to-know-about-mediation-arbitration-and-litigation/> [Accessed 31 August 2022]. Suff, R., 2022. Employment Tribunals | Factsheets | CIPD. [online] CIPD. Available at: <https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/tribunals/factsheet> [Accessed 31 August 2022].