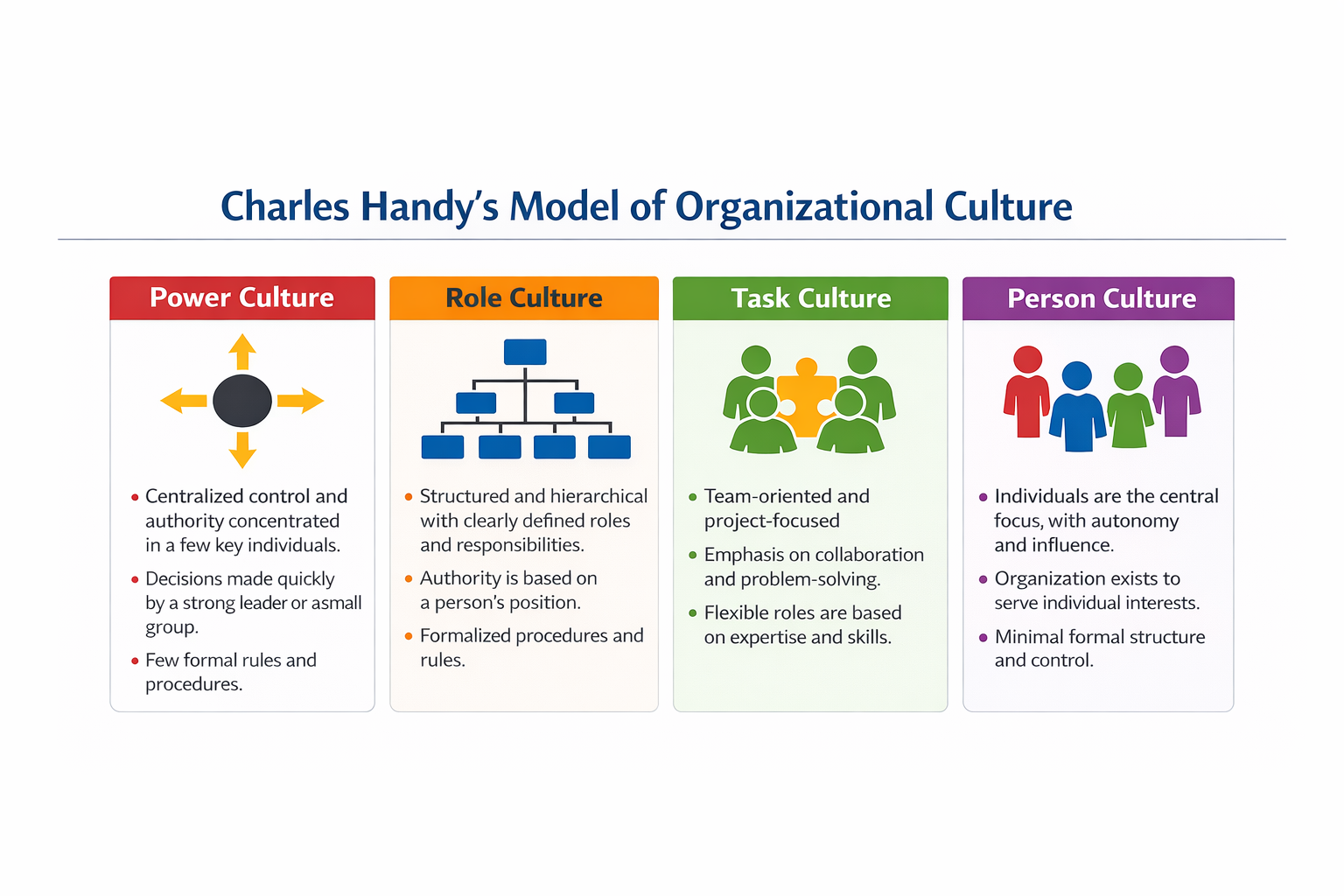

In the intricate tapestry of organizational life, understanding the underlying culture is paramount for effective leadership, strategic planning, and fostering a productive work environment. Charles Handy, a renowned management philosopher, provided a foundational framework in his 1978 book, Gods of Management, which continues to resonate with contemporary business practices. Handy’s model categorizes organizational cultures into four distinct types, each drawing parallels to ancient Greek deities, offering a vivid and memorable way to grasp their core characteristics . This blog post will delve into each of these four culture types—Power, Role, Task, and Person—exploring their defining features, advantages, disadvantages, and their relevance in today’s dynamic business landscape.

The Genesis of Handy’s Model: Gods of Management

Handy’s innovative approach to organizational culture stemmed from his observation that organizations, much like societies, exhibit distinct patterns of behavior, values, and power distribution. By associating each culture type with a Greek god, he not only made the concepts more accessible but also imbued them with archetypal significance. These cultural archetypes provide a lens through which to analyze an organization’s operational style, decision-making processes, and employee interactions .

The Four Culture Types: A Detailed Exploration

1. Power Culture (Zeus)

Symbolized by a web, the Power Culture is characterized by a centralized power structure, much like Zeus, the king of the gods, wielding ultimate authority. In this culture, power emanates from a central figure—often the founder or a charismatic leader—and spreads outwards. Decisions are typically made swiftly, relying heavily on the leader’s intuition and direct command rather than formal procedures .

Characteristics: Organizations operating under a Power Culture tend to have a flat hierarchy with minimal rules and procedures. Loyalty to the central figure is paramount, and success is often directly tied to the capabilities and vision of this individual. This structure allows for immense flexibility and rapid response to external changes, making it particularly common in nascent start-ups and entrepreneurial ventures .

Advantages: The primary advantage of a Power Culture is its agility and speed in decision-making. It can be highly motivating for employees who are closely aligned with the leader’s vision and enjoy a less bureaucratic environment.

Disadvantages: However, this culture carries significant risks. Its effectiveness is heavily dependent on the leader’s competence; a poor leader can quickly lead to organizational failure. It can also foster a climate of fear, limit individual initiative, and create bottlenecks if the central figure becomes overwhelmed . Examples include early-stage tech companies or small family-owned businesses where the founder maintains tight control.

2. Role Culture (Apollo)

Represented by a temple, the Role Culture embodies the principles of order, logic, and rationality, much like Apollo, the god of order and reason. Power in this culture is derived from one’s position within a clearly defined hierarchy, rather than personal influence or expertise. It is a bureaucracy in its purest form, emphasizing rules, procedures, and job descriptions .

Characteristics: Role Cultures are characterized by strict hierarchies, clear lines of authority, and well-defined roles and responsibilities. Stability, predictability, and security are highly valued. Employees are expected to adhere to established protocols, and performance is often measured by compliance with these procedures rather than individual innovation .

Advantages: This culture provides a high degree of stability, clarity, and security for employees. It is efficient in predictable environments and ensures consistent operations.

Disadvantages: Its rigidity, however, makes it slow to adapt to change and can stifle creativity and innovation. Decision-making can be protracted due to multiple layers of approval. Large government agencies, established banks, and traditional manufacturing firms often exhibit strong Role Culture characteristics .

3. Task Culture (Athena)

Symbolized by a net or lattice, the Task Culture is results-oriented and project-based, reflecting the strategic and problem-solving nature of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and warfare. In this culture, power resides with expertise and the ability to contribute to the successful completion of tasks or projects, rather than with a formal position .

Characteristics: Organizations with a Task Culture form teams to address specific problems or projects. Collaboration is paramount, and individuals are valued for their skills and contributions. The structure is flexible and adaptable, allowing for rapid deployment of resources to tackle new challenges. Expertise and flexibility are central, with coordination driven by project requirements and deadlines .

Advantages: Task Cultures are highly adaptable, innovative, and motivating for skilled professionals. They foster a sense of shared purpose and empower individuals to utilize their expertise.

Disadvantages: This culture can be expensive due to the reliance on expert teams and may lead to internal competition if not managed carefully. Examples include management consultancies, advertising agencies, and project-based engineering firms. Amazon, with its focus on results and team-led projects, can also be seen as embodying aspects of a Task Culture .

4. Person Culture (Dionysus)

Represented by a constellation of stars, the Person Culture is unique in that the organization exists primarily to serve the individuals within it, much like Dionysus, the god of individuality and freedom. The individual is the central point, and the organization acts as a supportive framework for their independent work.

Characteristics: This culture features minimal hierarchy and grants high autonomy to its members. Employees are typically highly skilled professionals who work independently, sharing resources like office space, administrative support, and IT infrastructure. What binds them are shared interests and values, rather than a strong organizational structure or common goal .

Advantages: Person Cultures offer immense individual satisfaction and freedom. They are ideal for highly specialized professionals who thrive on autonomy and self-direction.

Disadvantages: However, they are notoriously difficult to manage, as individuals may not feel accountable to a “boss” or a collective organizational objective. Pure Person Cultures are rare and often short-lived, typically evolving into other forms as they grow. Examples include law firms, medical practices, and academic research groups where individual practitioners collaborate while maintaining their independence .

Contemporary Relevance and Hybrid Cultures

While Handy’s model provides a clear categorization, it is crucial to recognize that real-world organizations rarely fit neatly into a single culture type. Many modern organizations exhibit hybrid cultures, blending elements from two or more types. For instance, a sales department might operate with a Task Culture, driven by targets and team collaboration, while the human resources department within the same company might adhere to a Role Culture, emphasizing compliance and standardized procedures .

The business landscape is also in constant flux, and organizational cultures are not static. Companies often undergo dynamic evolution, starting as a Power Culture under a visionary founder and gradually transitioning towards a Role or Task Culture as they expand and require more formal structures or specialized teams. The rise of remote work, for example, has challenged traditional Role Cultures, pushing organizations towards more Task-oriented approaches where results and deliverables take precedence over physical presence or rigid schedules .

Critiques and Considerations

Despite its enduring popularity and utility, Handy’s model has faced some criticisms. One common critique is its simplification of complex organizational realities. Critics argue that reducing culture to four archetypes might overlook nuances and the intricate interplay of various cultural elements within an organization. Additionally, the model, developed in the late 1970s, may not fully capture the complexities of globalized, digitally-driven organizations of today .

However, the model’s strength lies in its diagnostic power. It provides a valuable starting point for managers and leaders to understand their organization’s prevailing culture, identify potential strengths and weaknesses, and strategically plan for cultural change. By recognizing the dominant cultural traits, organizations can better align their strategies, leadership styles, and human resource practices to foster a more effective and harmonious work environment.

Conclusion

Charles Handy’s model of organizational culture remains a powerful and insightful framework for understanding the diverse ways in which organizations function. By personifying cultures through the Greek gods—Zeus, Apollo, Athena, and Dionysus—Handy provided a memorable and accessible tool for analyzing power dynamics, decision-making processes, and employee interactions. While organizations may exhibit hybrid forms and evolve over time, recognizing these fundamental cultural archetypes is essential for navigating the complexities of organizational life and building resilient, adaptable, and successful enterprises in the 21st century.